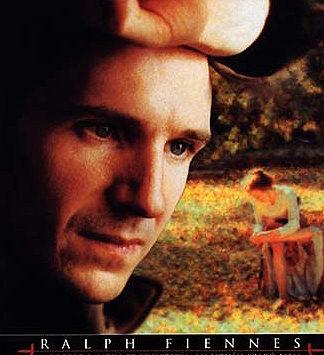

The following are reviews of "Onegin" and interviews with the actor. The film opened December 31, 1999 in the US, wider on later dates. The film opened on 19 November 1999 in the UK.

Click here for the front office review of "Onegin".

"Pushkin says in one of the stanzas, 'Who is he? Is he an angel? Is he a devil? Or is he just a charlatan?' He's almost unknowable. He's someone who's a bit lost and cut off, and he has removed himself from engaging with society and people. There's a line in the film that I really like, when he says, 'I'm not at home anywhere.' " (Excerpt from The Daily Telegraph, Thursday 18 November 1999)

November 28, 1999

Ralph Fiennes: On Screen, Over Lunch, Ever the Distant Hero

By Jennet Conant

He looks devastated. But then Ralph Fiennes always looks as if he is caught between deep melancholy and outright despair. It must be something about the roles he takes, or the way his mouth turns down at the corners, because his demeanor, while not exactly jaunty, is certainly sporting.

Told that a mix-up at the restaurant in his Manhattan hotel, The Four Seasons, means he'll have to wait a good half-hour at the bar before a table becomes available in the dining room, he says mildly: "You mean they are not going to clear the restaurant? Oh dear, what is the world coming to?"

This very private actor, who turns 37 this month, has earned a reputation for being somewhat insular and aloof since his astonishing debut in 1983 as the brutal Nazi concentration camp director in Steven Spielberg's "Schindler's List," for which he was nominated for best supporting actor. But after being swamped by acclaim following his next two films, "Quiz Show" and "The English Patient," the latter earning him a second Oscar nomination for best supporting actor, and being mobbed by fans for the entire sold-out run of "Hamlet" on Broadway in 1995, who could blame him for feeling a trifle antisocial? Besides, by Hollywood standards, just his refusal to move from London to Los Angeles would qualify him as remote.

In person, he merely seems shy. He makes several tentative stabs at polite conversation, stammering sentences that open promisingly and end up trailing off doubtfully. But he is unfailingly cordial, inquiring if the seating arrangement is acceptable and worrying that the bar area is too noisy. When he orders wine before lunch, he insists a reporter join him.

Over a glass of pinot noir, the famously intense leading man appears marginally more at ease than he did upon arriving, when his pale, angular face and blue-gray eyes were filled with dread of the coming ordeal. He leans back into the deep leather armchair, his loose-fitting olive linen shirt unbuttoned at the neck and his graceful hands -- which spring to life when he is telling an anecdote -- clasped in his lap.

He speaks so softly it is necessary to lean in close to catch his words. "I think it's rather nice to have an atmosphere to play off of, don't you?" he says, surveying the bustling lounge with a stage actor's fondness for mise-en-scene, a ghost of a smile on his lips.

So much of his new movie, "The End of the Affair," which opens on Friday, takes place in crowded cafes that it is impossible not to be reminded of Maurice Bendrix, the brooding, disaffected 1940s intellectual he plays in the film. "The End of The Affair" is based on the Graham Greene novel of the same name and was arguably the author's most autobiographical work, drawing on his illicit love affair with a married American named Catherine Walston.

The book is dedicated to her. The film, adapted and directed by Neil Jordan, focuses on the irrational, destructive forces that undermine the relationship, as the obsessed Bendrix succumbs to jealousy. Fiennes gives a controlled performance as the embittered novelist, whose simmering sexuality and self-contempt are barely contained by his elegant manners and stiff upper lip.

"That sense of understatement was the most defining thing," says Jordan, the Irishman whose films include "The Crying Game" and "Michael Collins." "It's very English, you know, and it's very Graham Greene."

Jordan says Fiennes was an obvious choice to portray the isolated, introspective novelist. "He has those eyes," Jordan says, adding that the casting of the film was a miracle of chemistry, with Julianne Moore playing the ardent Catherine and Stephen Rea (a favorite of the director) as her buttoned-down husband.

"Greene said that there was a splinter of ice in the heart of every novelist, so that even in the middle of their own tragedy or somebody else's, they were always taking notes," Jordan says. "It's the aspect of Greene's character I most wanted in the film, and Ralph played Bendrix like it was his destiny to watch and follow the events to their grave conclusion. There was something heroic in his refusal to take solace in anything. It was more touching in the end than anything else."

Jordan was apparently not the first person to recognize that the role of Greene's haunted literary hero was tailor made for Fiennes. What was very peculiar, as Fiennes tells it, was that during the summer of 1998 several close friends independently suggested that he consider playing Bendrix. One of them was Jonathan Kent, who had directed Fiennes in "Hamlet" and who advised him to read the novel, saying, "That's a part for you." Fiennes had only just gotten around to reading the book when, by coincidence, Jordan called him up and offered him the role.

"It was one of those rare occasions when everything just came together," Fiennes says. "I had always wanted to play a Graham Greene character like Scoby in 'The Heart of the Matter.' I just loved his compassion for human fallibility and self-deception and duplicity. His compassion for human weakness. I find that so moving, and I think it goes hand in hand with his faith," he says, referring to Greene's Roman Catholicism.

When asked about his own faith, Fiennes' is terse. "My mother was Catholic, I am not," he says, showing a glimmer of the fierce emotion he has famously demonstrated on screen. He bristles at the notion that he should necessarily resemble the wounded characters he has chosen to play in the past.

But over a hearty English lunch of beef and potatoes, and more wine, he concedes that with his next three films, he further expands his repertory of dark, romantic heroes. In addition to "The End of the Affair," there is "Onegin," which also opens next month, in which he gives a wrenching, Byronic performance as Evgeny Onegin, a jaded bachelor who learns how to love too late; the film is based on the epic 19th-century Russian verse novel by Alexander Pushkin.

And in Istvan Szabo's "Sunshine," to be released in the spring, he goes for broke, playing not one but three generations of a Jewish Hungarian family -- a grandfather, father and son -- bound by the same hopes, secrets and tragic betrayals.

"Ralph wants to learn the human problem," Szabo says. "He is a very intelligent person, and he is choosing roles that allow him to wrestle with moral problems, the real questions of character, and carry that message to the audience. He is someone who wants to say something. He is truly an artist."

Martha Fiennes, the actor's younger sister, who directed "Onegin," is somewhat amused by the public's fascination (particularly young women) with her brother's penchant for playing tormented types. "Really, I think Ralph is quite well adjusted," she says, sounding delighted at the opportunity to tweak her celebrated sibling.

"Ralph is not Onegin," she continues, in a more serious tone, "but he is attracted to certain types of characters, and he is interested in the dynamics of human behavior. I think what drew him to the story is that here is a man made conscious. And while there is tragedy in the missed opportunity, there is something great in the pain of that rite of passage."

"Onegin" is particularly close to Fiennes' heart. "It's funny, because as one critic commented, Onegin is the story in which nothing happens twice," he says. "But actually that's what I love about it, the nothing happening and the expectancy of (italics)something."(end italics) Closing his eyes for a moment, he recalls shooting the breathtaking opening scene, filmed in St. Petersburg, in which Onegin's horse-drawn sleigh flies across the vast frozen Neva. "I loved it," he says. "It's just one of those things, you feel so lucky afterwards that it happened in your life."

He first read Pushkin's verse novel in the early 1990s and was immediately struck by the cold, enigmatic figure of Onegin, who rejects the passionate overture of Tatyana, a spirited young girl played by Liv Tyler, and later pays a terrible price for his cynicism. The story stayed with him, and he gave a copy of the book to his sister, a director of commercials and music videos, making an offhand observation about the poem's cinematic potential.

From that casual comment sprang a film, seven years in the making, that Fiennes has championed, from the first crude storyboards he drew while on the set of a BBC film to the battle to find a distributor, an issue resolved only this fall. (It will be released by Samuel Goldwyn Films.)

He pushes away a double espresso that has gone cold. "I honestly don't know why it has been so hard," he says. "Whether it sounds like, 'Oh, there's Ralph Fiennes playing another tortured soul.' I don't know. My sense is, initially some people thought it was an indulgent, home-grown thing -- a rarefied family venture."

Fiennes is part of an increasingly famous family of artists, writers and actors. He is the oldest of six children (a seventh was adopted), and four of his siblings work in the film industry, including his youngest brother, Joseph, who starred in "Shakespeare in Love." His mother, Jini, was a painter and novelist who wrote under the pseudonym Jennifer Lash.

Although she was prone to wild mood swings -- she was once hospitalized as a young girl for hysteria -- she was extraordinarily loving and inspiring to her children. After her death from cancer in 1993, Fiennes arranged for her last novel, "Blood Ties," to be published posthumously. His father, whom he describes as a steadying influence, was a farmer who later became a photographer.

Throughout their childhood, money was scarce, and Fiennes clearly recalls his mother's struggle to bring up her children and find the peace and solitude she required to write. When they lacked the funds to send him to school, she educated him at home. It was his mother who first read "Hamlet" to Fiennes when he was 8, and gave him a recording of the play featuring Sir Laurence Olivier.

He was not immediately drawn to acting. As his interest in the arts grew, he thought of becoming a painter. He enrolled in the Chelsea College of Art and Design in London, but in the middle of the year he suddenly decided he wanted to become an actor. In 1982, he auditioned for the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Before long, he was making a name for himself at the National Theater in London.

"It just suddenly came to me very clearly," he says of his abrupt change of course. "It's not something I can rationalize even now." But his mother saw it long before he did. He recalls that after a high school play -- perhaps a performance of "Love's Labour's Lost" -- she turned to him on the walk home and said, "You know, if you want to, Ralph, you could be an actor."

"She wasn't like a stage mother," says Fiennes. "It wasn't that she wanted to see her boys shine on the stage and get the applause. I think she wanted us to be party to making those plays happen -- with Shakespeare at the forefront -- and to field those emotions and ideas for an audience. It was always the ideas in the play that would really excite her."

Her influence is apparent in the rather unorthodox career path he has charted in recent years, shunning traditional leading man roles in big Hollywood movies in favor of roles in smaller films and in the theater. Fiennes, who has spent the last few months preparing for his return to the London stage in a Shakespearean double bill of "Richard II" and "Coriolanus," admits that he felt quite buffeted by all the attention he received following "Schindler's List." His doubts crystallized the night he attended Tina Brown's lavish party (with the theme "The New Yorker Goes to the Movies") in Los Angeles, just before the Oscar ceremony.

"I was sitting at this table, and someone came up behind me and tapped me on the shoulder and I turned, and he said, 'When you're hot ... ," recalls Fiennes, twisting in his seat for dramatic effect. "Then he just walked away. I don't know who it was, but it was quite aggressive," he says, flopping angrily back in his chair. "I was so shocked."

It was during those alarming days, before he had adjusted to his overnight popularity, that his 12-year relationship with the actress Alex Kingston came unraveled. They have since divorced, and she now lives in Los Angeles and appears in the television series "ER."

For the last several years, he has been involved with Francesca Annis, a noted British stage actress 17 years his senior, who played Gertrude to his Hamlet.

"When the spotlight of the Hollywood film industry first turns itself on you, it is quite tantalizing," he says. "You can do no wrong, the whole world, everything, is yours. You're fed information, you're supported, surrounded by voices and noises that are encouraging. You know, it's all quite rosy."

He pauses and gives a slight shrug, happy to have left it all behind. He has no idea what he will do after touring with the plays, but says, "I think recently I feel calmer about the way I want to choose things."

Click here for a review of "The End of the Affair."

**********************************************

The Daily Telegraph

13 November 1999: A family affair

Friday 19 November 1999:Grand passions in an ice-cold

world

Martha and Ralph Fiennes deliver a searching and evocative adaptation of

Pushkin's classic tragedy Eugene Onegin

By Andrew O'Hagan

"It is not a picture of Russian life," wrote Nabokov of Eugene Onegin, "it is at best the picture of a little group of Russians, in the second decade of the last century, crossed with all the more obvious characters of Western romance and placed in a stylised Russia."

White Russian: dissolute hero Ralph Fiennes walks through a wintry St Petersburg of decadence and fading grandeur in Onegin, directed by his sister Martha For Nabokov - the stylists' stylist - as for Pushkin - the ultrastylists' ultrastylist - and for Tchaikovsky too, the great tragic narrative of Eugene Onegin is essentially a chamber piece, a story of wounded passions and anguished friendship among four young people trussed by honour and the manners of their time.

In the wrong hands this could have made for woeful cinema: an elongated episode of Friends, with samovars and shots of vodka on the side. It is never hard to muck up a masterpiece, and Onegin, with its simple but devastating sadness, could have been turned into some bodice-erupting stupidity contest set on a crumbling Soviet housing estate.

Mercifully the film is directed and produced by the family Fiennes: they love the text and have made a movie that is sensitive, grand, honourable in respect of Pushkin's vast moral inquiry, and yet very new and robust in itself. If the spirit of the present age is best captured by the likes of EdTV, then Onegin might be understood to offer something of that spirit's antidote: thoughtful - good God - philosophical - steady on - searching - yes - and tending towards an active engagement with the human soul. Stop the bus!

Onegin (Ralph Fiennes) is a bored and dissipated young-man-about-St Petersburg, a dandy and a saloniste, snacking on truffles and Limburg cheese, sighing into his claret. When a relative dies, he inherits a country estate with a large library. He goes to live there, and soon makes friends with Lensky (Toby Stephens), an affectionate young man who writes poems and loves a local girl called Olga.

Ralph Fiennes, more than any English actor working today, is equipped to convey an almost cosmic melancholy: even when he smiles broadly you sense he wants to die. He has a constant, flickering intelligence, and he is expert when it comes to performing the difficult, tense acrobatics of deep feeling. He is physically very present too, and, as Onegin, he transmits an almost Byronic, brute-force combination of joylessness and hope. His Onegin looks damned from the start.

In the country he soon catches the attention of Olga's young sister Tatyana, who comes to borrow a book - Rousseau's La Nouvelle Héloïse - and falls in love with him. Martha Fiennes, the director, has something of her brother's focus and restraint: in the scene where Tatyana writes Onegin a letter declaring her love, we feel the force of the young woman's desperate passion, and not from the words in her letter, but from the way the camera circles and entangles her, like a foreign force.

The camera goes in very close to the writing paper; we see the way it sucks at the ink, her hands smeared and trembling. The scene is made feverish and erotic: it chooses not to convey the force of her feeling with music or words, (as Tchaikovsky did) but instead, using camerawork, the director makes the moment both vivid and real.

Tatyana is played by Liv Tyler (last seen earlier this year in Robert Altman's Cookie's Fortune) and she brings most of what is required to the role. She is beautiful, with the skill of conveying a great deal with only a few words, and she comes to embody simple as well as complex variants of dignity. She is very good in the letter scene, and great in her long dejection; she enlarges as the film proceeds, and by the end, which I won't spoil, she comes to seem almost magisterial. Her eyes are by turns the eyes of a feasible redeemer and a trapped ghost.

The look and the feel of the film is what many will remember. The grand houses and palaces are - as they say in Habitat - "distressed", with paint peeling and dampness apparent at the corners. It is, as Nabokov said above, a stylised Russia, and the colours - slate-grey, eau-de-Nil, off-white - suggest a pre-Decembrist world of last-ditch decadence and fading grandeur.

The world outside is freezing cold. Martha Fiennes has done well to capture the wintriness of the setting; many of the scenes are like moments from Winterreise, with clouds of white and frozen lakes and solitary, hoary figures black against the snow. (At one point Lensky is shown singing Schubert in a stark wood.) As the incidents and passions in the story mount toward tragedy - concisely, unbearably almost - you feel the landscape even more. The weather carries all your foreboding.

The centre of the film is a duel between Lensky and Onegin. The scene is mesmerising and ice-cold: a hellish depiction of folly. This is one of the places in the film that brought criticism in Russia (along with much praise). Ralph Fiennes felt - as Pushkin did not - that Onegin should only fire after Lensky. This is a central moral moment that affects your sense of the whole narrative, and I have to confess I was dubious. Fiennes, sister and brother, are known to have disagreed about this: just how terrible an act is Onegin's?

I'll leave you to judge. It is right and good, though, that the film-makers felt free to work it out in their own way. There is only one thing worse than a bogus rip-off of a classic text - and that is a slavish, fearful, and overly faithful tribute to the mystery of literary achievement.

Onegin is alive in itself. It is a good film that is faithful to the sense and sensibility of the people that made it. What else is there?

For an article written by Ralph Fiennes on Shooting Pushkin, and more,

click here:

Ralph Fiennes and Pushkin's Onegin

**********************************************

And Shakespeare's coming . . . (Excerpt from The Daily Telegraph)

Next spring Fiennes will wear the hollow crown as Richard II at the historic (though soon-to-be redeveloped) Gainsborough film studios in London, a role he takes in repertory with Coriolanus. The two plays are being paired, says Kent, who is directing them, because, albeit written at opposite ends of Shakespeare's life, both are "about men of power who are incapable of exercising those powers properly".

"Coriolanus," he adds, "is a man who has a single-minded sense of duty and responsibility, and finds an almost samurai release in war but finds the small change of peacetime politicking distasteful. It's a good role for Ralph because he has a fastidiousness and fineness of spirit, a very pure sense of what he's about."

Will Fiennes ever make a full-blown comedy? Kent reckons he'd be "wonderful in a David Hare play" (which doesn't wholly answer the question), and cites a fundraiser in New York at which Fiennes read excerpts from P. G. Wodehouse. His silly-ass act apparently slayed the Americans. "The audience had to be helped from the auditorium," recalls Kent.

Richard II opens next April and Coriolanus next June at Gainsborough Studios, London (booking: 0171 359 4404).

FRONT PAGE |

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE |

THE HAMLET PAGE |

links/LINKS |

What's Up: STAGE |

What's Up: BOOKS |

What's Up: MUSIC |

What's Up: FILM |

Fictional Characters |

What's Up: |

Today's Special |

Sure We |