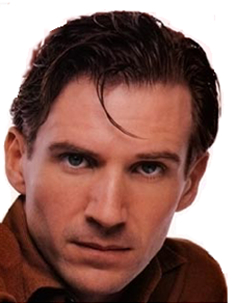

Russian authors have Ralph Fiennes in their grip; he's confessed great admiration for both Russian literature and Russian acting. He was thrilled to take Jonathan Kent's production of Anton Chekhov's first full-length play, "Ivanov," to Moscow after a successful run at the Almeida Theatre. In London, Fiennes' performance turned mild-mannered women into "Ivanov babes" and brought the contemplative play to a new audience.

Interest in Chekhov and his contribution to world literature flourishes. "The Undiscovered Chekhov" which contains 38 new stories and translated by Peter Constantine has just been published. (For a review, check the New York Times Book Review, March 14, 1999. pg. 12)

Fiennes, and his sister Martha, have turned their focus on Alexander Pushkin, also known as the "Shakespeare of Russia." In the article which follows, Fiennes explains that his idea to play Eugene Onegin, the "hero" of Pushkin's epic work, had its genesis long before he did Ivanov, some five years later.

This year, on June 6, 1999, Pushkin celebrates his 200th birthday. Fiennes is participating in a reading of Pushkin at Carengie Hall, in New York City. Pushkin's home town is gearing up for the big birthday bash. (Accommodations in nearby lodgings are sold out, we're told.) The opening of the film, for which Fiennes was executive producer, has been timed to coincide with the festivities. However, at least one early report had the Russian audience laughing at some historical inaccuracies, liberties and omissons. Whether or not film audiences less inclined to have proscribed ideas about the poem will like it, Fiennes seems geniunely dedicated to making a go of his film.

Pushkin won't have a say in the matter; he died on January 29, 1837, from wounds he received in a duel two days earlier on a snow-covered field outside St. Petersburg (thereby avoiding the death sentence imposed on him for the duel. Cheeky devil.) Where in Siberia is a Hollywood biopic when you need one?

Fiennes returns to the Shakespearean stage in 2000, in productions of Richard II and Coriolanus.

For the front office review of "Onegin", Click here.

For Ralph Fiennes--"He's not Onegin.", click here.

***************************************************

Shooting Pushkin

by Ralph Fiennes

It is January 13, 1998, and I'm on the overnight train from Moscow to Pskov, sharing a two-berth compartment with Andrei, my guide and interpreter. Our final destination is Mikhailovskoye, the country estate of Alexander Pushkin: my sister Martha and I are making a film of "Eugene Onegin," and this is the only important place in Pushkin's life that I have yet to visit. "Eugene Onegin" (oh-NYAY-gen) has been haunting me ever since I was introduced to it, in 1984, by Lloyd Trott, a teacher at my drama school [RADA] who passionately encouraged us to widen our reading. I watched an actress in the year above mine perform Tatyana's letter as a monologue, at Lloyd's suggestion; when he told me where the speech had come from, I immediately borrowed the Charles Johnston translation from the school library.

Pushkin greatly admired the poetry of Byron, but he is without Byron's cynical aloofness. in fact, this quality is more an attribute of Pushkin's eponymous hero, an aristocratic dandy who becomes bored with the amorous intrigues of St. Petersburg society and moves to the estate of his recently deceased uncle, in the country. There he meets a neighbor, the poet Vladimir Lensky, and these two begin a friendship of opposites: Onegin's cynicism versus Lensky's idealism. Lensky introduces Onegin to his fiancÚ, Olga Lagrina, and to her sister Tatyana. Pushkin gently mocks Lensky's naivetÚ, but he is full of tender affection for his heroine, Tatyana, when she writes the cool Onegin a letter declaring her love for him. Onegin pointedly rejects Tatyana, however, and soon afterward his rustic idyll comes to an end when he arouses his best friend's anger by dancing continually with Olga at Tatyana's nameday celebration. Lensky impetuously challenges Onegin to a duel, and is killed.

Reading "Eugene Onegin" for the first time, I was struck by the complementary arcs of its hero and its heroine, and I found myself imagining it as a play or a film. Of course, I wanted to play Onegin. His is the tragedy of the cynic. In the final section of the poem, after years of self-imposed exile, Onegin meets Tatyana again at a ball in St. Petersburg; she is now a sophisticated woman, and Onegin falls obsessively in love with her. He pursues her, and eventually confronts her in her own home, where Tatyana tells him that, although she still cares for him, she will remain faithful to her husband. Pushkin leaves the reader of his poem a witness to the crushed figure of Onegin, alone and rejected.

The cinematic potential of the poem crystallized for me only when I was filming "The Cormorant," a BBC film in Wales, in 1992. While waiting between camera setups, I drew crude, story-board style pictures of scenes from "Onegin"; I then wrote a loose treatment and showed it to Martha. Slowly the idea of a film grew between us. The producer Ileen Maisel championed our initial outline and introduced us to the writer Michael Ignatieff, who immediately saw its possibilities. By December, 1994, he had written the first draft of the screenplay.

In April of 1997, I made my first trip to Russia, playing Chekhov's Ivanov at the Almeida Theatre Company's production, which toured in Moscow; I visited the local sites specifically associated with Pushkin before joining Martha in St. Petersburg, where she was scouting locations. As I learned more about Pushkin's life, I was struck by the peculiar way that it echoed his great poem. In 1824, the young poet was exiled to the family's country estate because of his liberal views and inflammatory behaviour, a year before the Decembrist uprising, in which several of his friends were executed or deported to Siberia. It was at Mikhailovskoye that he wrote many of the central passages of "Eugene Onegin." In 1826, Nicholas I granted Pushkin permission to return to Moscow, where he was forced to accept a somewhat humiliating rank in the Tsar's court. At that time, the poet pursued a Moscow beauty, Natalya Goncharova, who could never fully respond to his desire for her but agreed to marry him, in 1831. Several years later, when the couple was living in St. Petersburg, Natalya attracted the attention of a young French officer, George d'Anthes, and his unabashed interest in her provoked Pushkin's jealousy. in 1837--despised by the aristocracy but already acknowledged as a great writer--Pushkin was shot by d'Anthes in a duel over the honor of his wife.

All the great Russian writers defer to Alexander Pushkin, but for non-Russian speakers he is elusive. I don't speak Russian, and, while Pushkin's short stories are entertaining and lightly ironic in translation, in his great poetic works--"Onegin," "The Bronze Horseman," and "The Gypsies"--the language barrier seems to prevent a complete union of reader and poet: the sense of Pushkin's words is inevitably being adjusted to facilitate the rhyme. Vladimir Nabokove, in the foreword to his deliberately literal version of "Eugene Onegin," writes that it is impossible to translate the poem--that it is best to sacrifice "elegance, euphony, clarity, good taste, modern usage, and even grammar" for something closer to Pushkin's line-by-line meaning. Nabokov's translation is non-rhyming verse form and, despite its eccentricities, his is the one I have come to like most. Nabokov also insists that anyone who really wishes to appreciate "Onegin" should learn Russian, and initially, I tried to take his advice. On the train to St. Petersburg, during my first visit, I would laboriously translate an odd line with the help of my Russian companions, but my only sense of achievement came from decoding Cyrillic letters; I couldn't' get near the sense of the poetry. Learning the Russian alphabet and a few phrases is one thing, but reading "Onegin" fluently in a short space of time--well, I couldn't. It was blithely ridiculous.

Now, on the train to Pskov, I am very happy to be cocooned in this compartment, leaving Moscow behind, mercifully free of telephones. And yet I am nervous about discussing the script of "Onegin" with Andrei. It has evolved slowly, and with difficulty, yet I tell myself that it has a coherence that it lacked before. Andrei quizzes me about our interpretation of the poem. He asks me why I think certain characters behave as they do. Pushkin is Russia's Shakespeare: to his countrymen, he is still alive, and the actions of his characters still provoke discussion and debate. Why doesn't Tatyana leave with Onegin? Does she really love her husband? Does Onegin really love Tatyana? I feel that my replies are inadequate, even though Martha and I have struggled with these questions for many hours.

Andrei goes to sleep, and I continue making notes on the script. Michael Ignatieff gave us a screenplay that was economical in exactly the way we wanted, but without Pushkin's commentary the poem's emotional clarity somehow eluded us. A young screenwriter, Peter Ettedgui, was instrumental in reshaping the material to reveal the arc of Onegin and Tatyana's relationship without losing the leanness that Michael had achieved. The greatest challenge is the dialogue: avoiding both pastiche and glaring contemporary idioms; finding the right tautness. After scrawling suggested amendments in black pencil, I sleep heavily for about four hours. At five in the morning, I wake up in a state of uncertainty and expectation, and try to imagine the landscape I'm passing through: I think of Pushkin's poem "Demons," in which spirits and devils pursue a sleigh at night, chasing it into limbo.

At 8:00 a.m. a radio is switched on from a central control somewhere on the train, and harsh, tuneless music forces us out of our beds. Soon the train stops: we have arrived at Pskov. It's still dark outside. We are greeted by Natasha, a striking woman with thick swaths of blonde hair. She has come from St. Petersburg with a driver and a minibus to take us to the estate. in the half-light, as we carry our bags across an ice-encrusted platform, a feeling of secret elation hits me. On the way to the minibus, I hear a metallic tapping behind me: a man is walking the length of the train, checking the wheels for metal fatigue. I cannot believe it: isn't this the same man who taps the wheels of the train when Greta Garbo's Anna Karenina arrives in Moscow? I stand watching him, and sense a peculiar blurring between the invented and the real.

Natasha has brought some breakfast for us: coffee in a flask, biscuits, bread, smoked salmon, ham, and cheeses. There is also some vodka. Drinking vodka in Russia is a reassuring inevitability. We draw up on the side of the road for twenty minutes to eat. The journey from St. Petersburg to Mikhailovskoye by horse and carriage took about six days in Pushkin's time. He would have stopped at roadside stations for the night; some of his letters were written during those overnight stops. The journey by road from Pskov to Mikhailovskoye takes about an hour and forty minutes, and as it gets brighter I can see the surrounding countryside more clearly. We pass frozen rivers, small villages of wooden houses that are painted different colors and decorated with carved woodwork. Some of these houses are warped by weather and time. I idly comment on their attractive simplicity. "You wouldn't last a night, I expect," Natasha says. "They are damp, with no water or plumbing, no electricity--and you would be smoked out by the stoves." The villages come and go between icy fields and stretches of silver birch and pine forest.

After driving for an hour and a half, we pull up in front of a run-down modern building. I am told that this is the conference center for Mikhailovskoye, which houses various Pushkin seminars and events. It is very desolate. Natasha goes inside to find our guide, and ten minutes later she returns with a friendly and enthusiastic-looking man, whom she introduces as Sasha. Sasha is the guardian of Mikhailovskoye. He gazes at us intensely, through glasses resting on his nose that soon turns pink the cold. There is a great warmth about him. Andrei is translating. He tells me that Sasha is speaking the most beautiful but slightly outdated Russian, and that he is addressing us "my angels." Sasha leans forward with purpose when I ask him questions, and his love for his work shines out of him. He quotes stanzas of "Onegin" by heart, and I wonder whether he carries the whole poem in his head.

We travel the short distance from the conference center to the estate of Mikhailovskoye itself, and park by a fence that marks the perimeter of the garden. I notice some builders' trucks, carpenters' tools lying by a shed, and a metal-framed bed propped up against a wall. Sasha tells us that Mikhailovskoye is being refurbished for the 1999 Pushkin bicentennial celebrations. The builders and decorators will stay here while they carry out their work. There has been no snowfall recently, and everything looks spare, naked and poor. In English, the word "estate" conjures up something quite substantial, even grand, but many Russian estates are quite modest.

As we walk through the gardens, the layout of Mikhailovskoye becomes clear. The house itself is a simple one-story wooden structure. On either side of it are two smaller building; one is a bathhouse, where Pushkin's nurse lived, and the other is the kitchen. Sasha explains that the house is not the actual building Pushkin lived in--that has been destroyed and rebuilt at least twice, this particular version having been constructed after the Second World War. The rooms are denuded of furniture. Things are being packed up for the refurbishment scheme, and big cases and tea chests occupy the center of the floor. I have already visited Pushkin's apartment in St. Petersburg, and although it was moving to walk through those rooms where Pushkin had lived, and to see the study where he wrote so many impassioned and impatient letters, it felt like a museum; its well-cared-for surfaces gave no suggestion of a home or a family life. Here, among the debris of storage boxes, tools, and midwinter detritus, I feel freer to reimagine Pushkin.

The house stands above the River Sorot. There is a steep bank from the doors at the back of the house to the river, which is partly frozen. We can see the small, dark silhouettes of fishermen on the ice, their lines disappearing through the holes they have drilled. Sasha tells us about a group of fishermen who were once caught on the ice as it broke up during a thaw and had to be helicoptered to safety. Did Pushkin stare out at the same antlike shapes poised above their fishing lines? Perhaps he walked down the steep path from the house and called to them on his way to the windmill, which lies about half a mile from the house. Pushkin carried a heavy stick with him when he walked, to keep his arm strong for holding a duelling pistol. There are many stories of duels fought by Pushkin as a young man--in one, he nonchalantly eats cherries as his opponent takes aim, fires, and misses.

As we head toward the frozen river, I am turning over in my mind the vast discrepancy between the immediate sensations of being here, absorbing Sasha's commentary, and the tortuous process of making a film. We are walking toward the windmill, and I ask Sasha if it has any connection with thewater mill at the site of the duel in "Onegin." He's not sure, but I ask him to describe the duel, the ritual--the events as Pushkin describes them. He punches a finger into the frozen snow at our feet. "Here is Onegin, here is Lensky, the barrier is here--about ten paces. They walk toward each other. Onegin fires first."

"Doesn't Lensky fire first?" I ask.

"No, no, Onegin," Sasha replies.

"Are you sure?" I say.

"Yes, yes, Onegin shoots first and kills him."

To my embarrassment, I see that I have been so preoccupied with the script that I have forgotten what changes we have made in key areas of the story. This moment is the beginning of an unwinding distrust within me about the way literature is adapted into film. Even with the best of intentions, this appropriation is often a distortion or a mutation for the sake of audience satisfaction and accessibility. Martha and I have tried to remain faithful to Pushkin's poem, but we have also been told that a contemporary audience may not sympathize with Onegin, or may not understand why Tatyana would write him a passionate love letter on the basis of one meeting: how are we to make these things credible?

In our script, Onegin arrives late for the duel, as he does in the poem, but he makes a substantial attempt at reconciliation, which Lensky refuses. Lensky then fires first and wounds Onegin,whereupon Onegin returns fire, but with a look of deep reluctance on his face. My conversation with Sasha at Mikhailovskoye spurs me to reexamine this scene, and, on reflection, our script seems a betrayal of the original. In the poem, Onegin is more glib, as if any show of remorse were a sign of weakness:

Malevolently now,

similar to hereditary foes,

as in a frightful, enigmatic dream,

they for each other, in the stillness,

prepare destruction coolly.

Onegin's "look of deep reluctance" in our screenplay now seems sentimental; the poem's portrayal of this confrontation is far more disturbing and realistic. Only when one man lies dead should the barbarity of the duel sink in--not before.

Weeks later, when we shoot the scene--by a small lake in the south of England--my misgivings return, and I am unable to give Onegin a moment of conscience immediately before he pulls the trigger. From my position on the jetty we have built, I see Martha, frustrated at my intransigence, gesticulating on the shore with the producers. I am caught between my strong instinct not to betray Onegin as I've come to see him and the call of collaboration with Martha, and I feel alternately guilty and determined. How Martha and I understand this scene will continue to change in the editing process, as we debate the many plausible versions of the duel, trying to convey the way in which the ritual imposes itself on the protagonists. In our final cut, the duel is almost a moment of time suspended, in which the characters have no choice.

After our walk around the grounds at Mikhailovskoye, Sasha takes us to a neighboring estate called Trigorskoye. This was the home of the Osipov family, and it has been suggested that the Osipovs provided inspiration for the Larins: there is a garden bench at Trigorskoye known as Tatyana's bench. Pushkin describes Tatyana rushing from the house to the privacy of the garden when she thinks that Onegin has come to respond to the letter. Suddenly, he appears before her and tells her that he cannot reciprocate her feelings and is not made for married life. Sitting on this legendary bench at Trigorskoye, I try to visualize their encounter.

Like Pushkin's home, Trigorskoye is being given a bicentennial spring cleaning: there are tractors, earthmovers, and piles of builders' rubbish. I know that in the coming summers many people will visit these places, and perhaps, over the years, they will acquire a patina of archival polish. But on this day, January 14, 1998, there is virtually no one here--there are only ghosts, and my visit is a loose ribbon of possible imaginings. I remember a pastel sketch by the Russian painter Serov, who portrayed the poet on horse back riding off into the country. In his sketch we see Pushkin hurrying away from us, perhaps to visit with the Osipovs, where he will meet Anna Petrovna Kern, with whom he is infatuated. Or maybe he is simply riding out to free his mind and to escape the claustrophobia of his home. I feel that I, too, may glimpse him at any moment.

Eight weeks later, we are shooting in St. Petersburg, and it is my first day of playing Onegin. I have set my alarm clock for an hour earlier than necessary: I want to read the poem one more time. We've brought fake snow with us, but I'm crossing my fingers that there will be no thaw, that the Neva will stay frozen, that the slight snowfall of the previous evening will have increased during the night. We are on a very tight shooting schedule. I glance out the window and uncross my fingers: the snow is falling thicker and thicker. The sky is a milky gray--a perfect light. Everywhere, the architecture of St. Petersburg is outlined in white, and seems to promise the world I have stared at in so many paintings.

Our morning's location is the Peter and Paul Fortress, a forbidding defensive embankment built by Peter the Great. The Neva is frozen. The dark shapes of the fortress and the white of the snow look extraordinary. No one can believe our luck. We don't speak of it. There is an atmosphere of concentration and purpose. The scene is relatively simple: Onegin, unsettled at having reencountered Tatyana, walks through the city alone. Each ritual of preparation for the shot is heavy with meaning for me; makeup, hair, wardrobe, actor are like pieces of a puzzle that are finally coming together to form Onegin. Later, I will be able to remember only images and sensations: the frozen river; Martha in her white fur hat and padded silver jacket; the camera crew all swathed in Arctic clothing; my top hat, flapping cloak, numb fingers, runny nose.

In an ideal world, Martha and I would have shot every frame in Russia, but we could afford to remain there only a week. In the end, we shot the frozen Neva twice: once in St. Petersburg, when it really was the Neva and it really was frozen, and once in Leavesdon, in Hertfordshire, England, on a disused airfield. There, using exaggerated perspective, our designer, Jim Clay, created a sleigh ride and a nineteenth-century ice-skating party. Our days in St. Petersburg were thrilling, but would an "Onegin" shot entirely on location have made a better film? Not necessarily. Not one scene of "Dr.Zhivago" was shot in Russia, and in an earlier adaptation of another Pushkin story--"The Queen of Spades"--St. Petersburg was replicated at Welwyn Studios, in North London. Constraints of money and time can fuel all the bizarre energies of cinematic artifice, giving it a reality that is more powerful because it must suggest what it cannot show.

By the end of March, Onegin's world is being recreated at Shepperton Studios, near London. One afternoon in April, my English agent, Larry Dalzell, comes to visit me there, and I ask him if he would like to see the set. I know they are filming the ballroom sequence, which is when Liv Tyler, as Tatyana, makes her entrance, having been transformed from a country girl into a St. Petersburg princess. I take Larry downstairs, through the heavy doors of the soundstage, and across some electric cables, to a small doorway onto a balcony from which one can look down onto the dance floor. He gasps as he takes in the scale of the set: the vast columns dwarf the dancers, and the floor is a kaleidoscope of uniforms and ballgowns.

There is an anticipatory moment of silence: Martha is about to go for a take. The assistant director, Tommy Gormley, calls for "playback," the music of the polonaise begins, and the room comes alive: people dance, talk, bow, acknowledge one another. Then, to our right, double doors open and Liv Tyler, serene and beautiful as Tatyana, walks into the room. People smile and step aside for her, and a Steadicam follows behind almost respectfully, like an unusual bodyguard. Larry sees no lights being rigged, no rehearsal, just an extraordinary fluid movement of camera and actor. This is cinema as theatre. Then the assistant director calls "Cut!" and the spell is broken.

During my visit to Mikhailovskoye, I could not have guessed how Pushkin's characters would beinterpreted and given life, or how the ballroom scene would look, or how the two scenes of rejection would find their balance in the film. Two months later, those experiences of walking through an avenue of linden trees in Pushkin's gardens with my Russian companions or taking turns photographing one another on Tatyana's bench seem like moments of innocence.

Our January pilgrimage with Sasha ends at the monastery where Pushkin is buried. Pushkin's tomb, which is outdoors, is covered with a kind of Perspex lid to protect it from frost, and it appears to be squeezed between the exterior wall of the church and the parapet that separates the churchyard from the road. Sasha tells us the authorities were nervous that the presence of Pushkin's coffin in St. Petersburg might lead to a popular--potentially inflammatory--display of grief, and so it was taken posthaste to Mikhailovskoye. Unlike all the monuments to Pushkin I have seen in St. Petersburg and Moscow, this tomb is plain and unadorned. Natasha has brought some flowers with her, and an apple. She gives us each a stem as an offering to Pushkin. Just before we move away, Natasha places her apple on the edge of the tomb.

I do not speak Russian, and I do not understand it, but I understand this gesture. It says that a dead writer can still be a contemporary writer--that he can move us now, at any moment. Changes of time, place, custom, manners, and language can alter our perspective on a great writer, but they cannot extinguish the power of his words on the page. Our film, however wayward, is a response to that power. In "Onegin," after all, the reader is addressed directly, as the poet's friend and partner. It's impossible to read Pushkin's intimate farewell at the poem's end and not feel that he is speaking to you personally:

Whoever you be, O my reader--

friend, foe--I wish with you

to part at present as a pal.

Farewell. Whatever you in my wake

sought in these careless strophes--

tumultuous recollections,

relief from labours,

live pictures or bon mots,

or faults of grammar--

God grant that you, in this book

for recreation, for the daydream,

for the heart, for jousts in journals,

may find at least a crumb.

Upon which, let us part, farewell!

Find out more here:

Filming Russia's Sacred Text The Economist

Fiennes' "Onegin" gaffes lead to media cold war The Hollywood Reporter on the slightly ruffled Russians.

"Pistols at 20 Paces"--Review by Richard Lamb of the book "Pushkin's Button," by Serena Vitale, New York Times Book Review, March 7, 1999, pg. 27.

"Back By Popular Demand"--Review by Donald Fanger of the book "The Undiscovered Chekhov," by Anton Chekhov, New York Times Book Review, March 14, 1999. pg. 12.

The film opened in the UK on 19 November 1999. It opens in the US on December 31, 1999.